Lexington Park, home of the St. Paul Saints, in 1952.

Twin Cities Ballparks

Lexington Park, home of the St. Paul Saints, in 1952.

Compiled by Stew Thornley

Author of On to Nicollet: The Glory and Fame of the Minneapolis Millers

Although the first tenant of Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington, Minnesota, was a minor-league team—the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association—it was clear that the Met was constructed with a major league team in mind. Another new stadium opened in 1957, one year after Met Stadium. It was Midway Stadium in St. Paul. This served the St. Paul Saints, the Millers’ Twin Cities counterpart in the American Association. Some had designs on this one also hosting major league baseball, although that never happened.

Prior to the Met and Midway were a covey of ballparks that were a big part of the rich minor league heritage in the Twin Cities. On top of that, two of these ballparks (they were so modest in structure they could hardly be called stadiums) also held major league distinction: one as a host to a major league team and one as the site of a major league game.

The first, the Fort Street Grounds, was home to a St. Paul team in 1884 that finished its season by playing nine games in the Union Association, at that time in its only year as a major league. It was hardly a remarkable story but it was significant in that it was Minnesota’s first major league team. However, all its games in the Union Association were on the road; thus the Fort Street Grounds was the home field for a major league team although it never hosted any of its games during the time it had this status.

With Athletic Park in Minneapolis, it was the other way around. No major league team was based in Minnesota from the period of 1889 to 1896 that Athletic Park stood in downtown Minneapolis. Even so, this tiny park served as the host for a major league game in 1891.

These, and many other ballparks, are a key part of the history of professional baseball in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

Early Minneapolis Ballparks

The first fully professional league that Minnesota teams played in was the Northwestern League of 1884. The Minneapolis team played at a structure erected in the vicinity of 17th Street between Portland and Chicago avenues. The ballpark contained a grandstand that could seat 1,300 and two pavilions that accommodated another 1,000 each. The grandstand was fitted with “dressing and retiring rooms for both gentlemen and ladies and bathrooms for the players,” according to the Saint Paul and Minneapolis Pioneer Press of Monday, May 19, 1884. The grounds were supplied with 100 posts for horses, and the facility was enclosed with 12-foot-high fences.

Within a couple of years, the Millers were a couple of miles away, playing in a small ball field by the Milwaukee railroad lines just off Lake Street and Minnehaha Avenue.

Athletic Park The Millers produced a winning record their first year at Athletic Park, made a run at the pennant in 1890, and got off to another good start the following year. However, while they were in first place in August of 1891, the Miller’s pennant hopes crashed and their season came to a premature halt. The team was forced to disband because of financial problems, leaving Minneapolis without professional baseball.

To fill the void, the Milwaukee team of the American Association, a major league in its final year of operation, transferred its final series of the season, against Columbus, to Athletic Park in Minneapolis. The teams’ reasons for playing a neutral site game may have gone beyond the altruistic notion of providing entertainment to baseball-starved fans in a city that had lost its team. According to the St. Paul Pioneer Press, “Having lost all prestige in their own towns the two teams sought to run up to Minneapolis and replenish their exchequers.”

No one’s exchequer found much replenishment, though, as unbaseball-like weather prevented two of the games. But on October 2, 1891, despite heavy clouds that threatened rain or snow, Minnesota hosted its first—and until the Minnesota Twins arrived in 1961, its only—major league game as Milwaukee beat Columbus, 5-0. The Brewers’ Frank “Red” Killen, who had started the season with Minneapolis and had hurled a no-hitter for the Millers the year before, held the visitors scoreless on six hits.

Columbus’ best scoring chance came in the third when Jack Crooks doubled and went to third on Tim O’Rourke’s sacrifice; however, Crooks was nailed at the plate trying to score on Charlie Duffee’s fly to Tom Letcher in right. The Brewers got on the board in the fourth when Eddie Burke was hit by a pitch, took third on Jack Easton’s wild pickoff attempt, and scored on a passed ball with two out. Milwaukee broke the game open in the fifth with four runs, getting four of their five hits that inning, including two doubles, a run-scoring single by Killen, and a two-run homer by Jack Carney. Burke scored the final run on another passed ball.

The teams then escaped the cold weather in Minneapolis, going back to complete their season with one last game in Milwaukee on October 4. This also proved to be the end of the American Association as a major league; it disbanded soon after with the National League absorbing four of its teams. But in its final days, the Association did provide Minnesota with its first major league game.

The Minneapolis Millers continued to be the main attraction at Athletic Park, and, a few years later, produced a slugger able to take full advantage of the ballpark’s tiny dimensions. First baseman Perry Werden hit 42 home runs in 1894, an unheard of total until he topped it by hitting 45 the following season. From that performance, Werden held the organized-baseball record for home runs in a single season that lasted until Babe Ruth took up the business more than two decades later.

Werden wasn’t the only heavy hitter on the team; the mighty Millers averaged over 10 runs scored per game in 1894 and 1895. However, their pitchers were equally adept at giving up runs, and the Millers finished no higher than fourth either year. The frequent parades across home plate might have continued indefinitely, but in May of 1896 the Millers were given their eviction notice from Athletic Park. The land on which their grounds stood, only one block from the main street of Minneapolis, had been sold and they were given 30 days to find a new home. On May 23rd, the Millers played their final game at Athletic Park, then left on a lengthy road trip, not knowing where their new home would be when they returned.

It might seem Minneapolis was quickly going through ball parks around the turn of the century. It was no different in St. Paul.

Fort Street Grounds Finally in early May a site was selected just off Fort Street (also known as West Seventh Street) on the north side of the Short Line Railroad Tracks. The park was bounded by St. Clair Avenue on the north, Duke Street on the east, Oneida Street on the west, and the railroad tracks. (Fire insurance maps aren’t conclusive but seem to indicate that home plate was in the southeast corner of the lot, meaning that the right field fence was parallel to St. Clair with the left field fence running along Oneida Street.)

The Saint Paul and Minneapolis Pioneer Press reported that directors of the St. Paul club contracted for work “necessary to put the grounds in order” on Saturday, May 17. The plan was for a grandstand to seat 1,200 with open stands to hold an additional 1,200. It appears the project was completed in time—in all of the 23 days allocated for construction—because the first game was played on schedule on Monday, June 9 with Quincy beating St. Paul, 6-1, before 2,000 to 2,500 fans.

Somehow the capacity swelled when the Minneapolis Millers crossed the river for a game with the St. Paul team. Three of St. Paul’s star players were from Minneapolis but had been shunted away from their home city as the Miller owners eschewed local talent, opting instead for “real ball players.” As a result, Billy O’Brien, Charley Ganzel, and Elmer Foster were in St. Paul uniforms as more than 4,000 fans worked their way into the Fort Street Grounds for the first meeting between the Twin City rivals (although some estimates have the crowd as small as 1,200). Led by the Minneapolis exiles—Foster on the mound and Ganzel behind the plate—St. Paul beat the Millers, 4-0.

The Northwestern League’s artistic performance was not matched with the same success off the field as most of its teams were financially unstable. Bay City (Michigan) was the first team to disband, on July 25. By mid-August only three teams remained and three weeks later only Milwaukee and St. Paul were left. The league’s final game was played between the two survivors on September 7. St. Paul left on a barnstorming tour to the west while Milwaukee indicated a desire to close out its season in the Union Association, in its only season as a major league. Like the Northwestern League, the Union Association had seen its share of teams disband in the course of the season and was always on the lookout for clubs to replenish the ranks. It eventually admitted both Milwaukee and St. Paul.

St. Paul played its first major league game on Saturday, September 27, losing in Cincinnati by a score of 6-1. St. Paul played two more games in Cincinnati, moved on to St. Louis for a two-game series, then went to Kansas City for three games before coming back to St. Louis for what turned out to be its final game. The Fort Street Grounds, erected so quickly and having served so ably, was still considered the home ball park for St. Paul even though the team never played a game there during the time it was in the majors.

Dale and Aurora Grounds Comiskey needed a place for his team to play. In early April 1895, he began the process to build a ball park in the block between Dale and St. Albans streets and Aurora and Fuller avenues.

The grandstand and two sets of bleachers provided 3,000 seats within the ballpark. During some exhibition games played before the regular season, though, Comiskey discovered that another 1,000 people were able to watch the game from a hill along St. Albans Street. Of course, these were not paying fans, and Comiskey moved to put an end to their freeloading by erecting additional stands on that side of the field. On the morning of the first regular-season game, Tuesday, May 7, 1895, the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported, “The advantageous position on the hill has been blocked by a high row of seats on that corner of the park, and that congregation of person who would otherwise probably not pay their half-dollar to see the game will be disappointed.”

Prior to the first official game, the Saints and the Milwaukee team toured the city in a couple trolley cars, headed by a car containing a band. The parade ended at the ballpark, where the teams worked out for a couple hours before the game began at 3:30. Tony Mullane started on the mound for the Saints and also homered in the game, which was delayed by rain for about a half-hour in the third inning. Despite rain that caused a 30-minute delay in the third inning, the attendance was 3,000, and the Saints won 18 to 4.

Although Comiskey eliminated the free view from St. Albans, he quickly discovered another problem, according to the article “When Charlie Comiskey Came to St. Paul” by the Junior Pioneer Association (on file at the Minnesota Historical Society): “Within a few weeks the small fry had bored more than 200 peep-holes in the fence. Comiskey merely grumbled, ‘Boys will be boys,’ and created a second fence six inches inside the other.”

This ball park was called, alternately, the “Dale and Aurora Grounds” or, more simply, “Comiskey Park.” In addition to owning and managing the Saints, Charles Comiskey played 17 games as a first baseman, which marked the end of his career as an active player.

The Saints had another problem with this park than just fans getting a free peek at the game. Some people in this neighborhood objected to Sunday baseball and got a judge to grant an injunction prohibiting games on Sunday. Comiskey arranged to have the Saints play a couple of Sunday games at the Minnehaha Driving Grounds in Minneapolis.

Athletic Park on State Street (In 2002, architectural historian Paul Clifford Larson found the building permit for State Street Park and discovered that the architect for the ballpark was listed as the firm of Gilbert and Taylor, consisting of James Knox Taylor and Cass Gilbert. Gilbert later designed the Woolworth Building in New York and the Supreme Court Building in Washington as well as the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul. It’s not clear if Gilbert actually had a role in the design or if it was handled by one of the firm’s draftsman, although Larson said it is clear that Gilbert was not involved in supervising the construction, although that was commonly the role of an architect at that time.)

The Western League’s president, Ban Johnson, wanted his organization to eventually become a major league. That dream was realized. In 1900 Johnson changed the name of the league to the American League. The following year it achieved major league status and, of course, the American League is still alive and well today and even has a Minnesota team—the Twins—in it.

Although both Minneapolis and St. Paul had teams in the American League’s precursor, neither city was still in the league by the time it became a major league. Before the 1900 season, Charles Comiskey moved his St. Paul team to Chicago, where it exists to this day as the White Sox.

Some local speculation exists that it was the onerous blue laws, prohibiting Sunday baseball in some locales and causing so much inconvenience to the teams, that drove Comiskey out of St. Paul and cost the area a major league team around the turn of the century.

While such legends make for good conversation, the truth is that Western League president Ban Johnson never had any intention in keeping a team in such a distant outpost as St. Paul. In the two years that the Western League made its transition to the American League, many teams were moved from smaller Midwestern cities to Eastern metropolises.

Anyway, the Saints had already solved their Sunday problem in 1897 by moving to a new park in a neighborhood where the residents didn’t care what day of the week baseball took place.

The Pillbox According to the article “The Downtown Ball Park” by the Junior Pioneer Association, “The ‘pill-box,’ as it was generally called, was not a thing of beauty, and few pictures of it exist. A high fence surrounded the park, topped by a wire screen about 20 feet high. Home plate was in the south-east corner of the block, as the management did not wish to antagonize the people in the area by having the entrance at Minnesota and 13th. The stands were only 10 to 20 feet from the base lines, which ‘gave the spectators a good view of the players,’ according to the papers, although home plate was not visible from some points in the stands. When the umpire worked behind the plate, he had his back against the screen in front of the stands. Catching high fouls was impossible. The right fielder played with his back against the fence, and was only a few feet behind the second baseman even then. A 3-bagger was practically unknown, and would only result from a ball taking a freak bounce off a fence post or thru some other accident. There were plenty of 2-base hits due to special ground rules; balls hit over the right and left field fences counted for two bases, and home runs were scored only over a limited area of the center field fence.”

Except for Sunday games, which were played at Lexington Park, the Pillbox was the regular home of the Saints through the 1909 season. (The Saints played one Sunday game at the Pillbox, in May 1907, an experiment to see how disruptive Sunday ball would be to the neighborhood. The conduct of the spectators would determine if more Sunday games could be played downtown. The St. Paul Pioneer Press quoted Saints manager Ed Ashenbach as telling the fans, “We hope to play here again, and I hope you will not make any more noise than is necessary.” Although the Pioneer Press reported that the game was “perhaps the most orderly crowd that ever attended a Sunday baseball game in this city,” it was the only Sunday game played at the Pillbox.)

In addition to the Saints, the Pillbox was home to an all-black team, the St. Paul Colored Gophers, and hosted a series in 1909, billed as the “world’s colored championship,” in which the Gophers beat the Leland Giants of Chicago.

While the Minneapolis and St. Paul teams played at several parks with brief service, each had one special one that lasted longer than just about all of its other ball parks combined.

Opened and closed a year apart, Nicollet Park in Minneapolis and Lexington Park in St. Paul each lasted 60 years, a record unlikely to be matched in the Twin Cities as rapid obsolescence has become the norm with modern professional stadiums.

Such longevity appears to be particularly remarkable because of the era in which the ball parks were constructed, when wood was the primary building material, making the structures were vulnerable to fire. Twice damaging blazes struck Lexington Park, the second time destroying most of the structure in 1915, but Nicollet Park managed to avoid this type of disaster long enough to make the transition to more permanent materials.

Nicollet Park Although spacious compared to the band box that it had abandoned, Nicollet Park soon became known for its modest dimensions, particularly the short distance to the right-field fence, which ran along Nicollet Avenue and was an easy target for strong lefthanded hitters. Although slightly farther away from home plate, the left-field fence, separated from Lake Street by a row of buildings, was also reachable.

Home plate was in the southwest corner with a grandstand that extended down the down the third-base line along Blaisdell Avenue and down the first-base line, along West 31st Street, which separated the ball park from the streetcar barns and garages of the Twin City Rapid Transit Company.

According to figures cited in a 1951 article when Nicollet Park was sold, the ball park covered approximately four acres with 450-foot frontages on Nicollet and Blaisdell avenues and 379 feet of frontage on West 31st Street.

Nicollet Park had a pennant winner its initial season as the Minneapolis Millers finished first in the Western League, and it continued as the home of the Millers when the team became a charter member of the American Association in 1902. Over the next 10 years, the ball park got a new look.

The main grandstand was rebuilt prior to the 1909 season with a tier of box seats put in front of the regular seats, necessitating the moving of the players benches as well as the press box. “A private box has been built for the newspaper scribes and this season will prove a sad one for the nosey fan who has always insisted on hanging over the back of the press box to show the pencilpushers where they are wrong in their scoring,” wrote the Minneapolis Journal of April 20, 1909. In addition, repairs were made to the third-base bleachers, and the first-base bleachers were converted into a grandstand and covered. The main entrance was also changed to the 31st Street side of the ball park. “When the fans turn out Thursday afternoon to get the first glimpse of the 1909 Millers on the home grounds,” reported the Journal, “they will hardly recognize the place.”

An even greater facelift took place following the 1911 season, a $30,000 renovation that included a new grandstand and bleachers that had “a solid concrete base with iron columns supporting an ornamental red tile roof,” according to the November 25, 1911 Minneapolis Tribune. The main entry remained at the corner of 31st Street and Nicollet Avenue, in the right-field corner, with a walkway running underneath the grandstand to the seats on the third-base side and an inclined walk, replacing stairs, taking fans into the stands on the first-base side of the field. The seating capacity of Nicollet Park swelled to approximately 10,000, two-and-a-half times what it could originally hold. The headline on the December 3, 1911 Minneapolis Journal proclaimed “Minneapolis Fans Will Not Recognize Their Old Ball Yard Next April,” the second time in fewer than three years that the newspaper made this claim.

The architect for the renovation was Harry Wild Jones, who had designed homes, churches, and commercial buildings in the city. The hiring of Jones “signaled the team s strength as a business enterprise and demonstrated a kinship to the Minneapolis elite who built commercial monuments in the most popular styles of the day,” wrote Augsburg College professors Kristin M. Anderson and Christopher W. Kimball in an article for Minnesota History magazine.

Besides the new grandstand, the board fence surrounding the grounds was replaced by a 14-foot-high concrete wall topped with red tile, but the most prominent addition was a Tudor-style entry building at the on the corner of 31st Street and Nicollet Avenue, topped by a steeply pitched red-tile roof. In addition to the ticket windows and turnstiles at street level, the building had management offices, which previously had been housed in downtown Minneapolis, and locker rooms on the second floor.

To accommodate the new structure, the grandstand in the right-field corner was angled toward the field. The foul line intersected with the stands, 279 feet from home plate. The roof over the grandstand created an overhang in right field, which at times could affect play. One example occurred in 1953 in the afternoon game of the Independence Day doubleheader. Trailing the Saints, 9-8, the Millers had two out and nobody on in the ninth when Clint Hartung walked and Ray Katt lifted a soft fly toward right. It appeared Saints right fielder Walt Moryn right fielder would be able to catch the ball until, as described by Halsey Hall in the Minneapolis Tribune, “the breeze caught it and it came down, scraping the screen UNDER the jutting grandstand roof. But it had kissed that screen so gently and was a home run, Raymond completing that most joyous jaunt of all and being mobbed by fans and teammates.”

Longtime fan Fred Souba says he remembers Kelley sitting in the front row beyond first base with his Dalmatian (sometimes more than one), but he does not recall any instances of the dogs affecting the game in any manner and certainly not by coming onto the field.

There were also stories of long home runs to right setting off alarms of businesses across Nicollet Avenue from the ball park, and at least one of these is documented. On Saturday night, August 26, 1950, Johnny “Spider” Jorgensen won a game for the Millers with a two-run homer in the last of the ninth off St. Paul s John Van Cuyk. According to the St. Paul Pioneer Press, “The ball sailed across Nicollet Ave., crashed through the heavy plate glass door of an appliance shop [Johnston s Appliance] and set off the burglar alarm.”

Lexington Park

On the southwest corner of Lexington Avenue and University Avenue, approximately one mile west of the park the Saints had been using off Dale Street, the ball park occupied a lot 600 feet square, large enough to provide for generous field dimensions.

The St. Paul Pioneer Press was effusive in describing the new grounds in a story the day Lexington Park opened, on Friday, April 30, 1897: “St. Paul fans will see a ball ground that is not excelled in the West, and those who are familiar with the National league parks say that few, if any, of them surpass the St. Paul park. Some of them have stands that will seat more people, but so far as the field itself concerned and the general accommodation of the public, there is probably nowhere in the country a superior.”

The newspaper s praise continued in the next day s edition with a description of the first game, a 10-3 Saints win over Connie Mack s Milwaukee team: “Those of the fans who had not paid an anticipatory visit to the park fairly gasped with amazement and delight as they entered, and when they got fairly located in bleachers or stand and gazed out over the wide open plain of rich green and brown earth, as smooth as a billard [sic] table, their admiration knew no bounds. The more the arrangements and conveniences of Lexington Park are studied the stronger becomes the impression that it is not excelled anywhere in the United States.”

The only complaint offered was that the extra street cars dropped passengers at the corner of University and Lexington. While this would seem to be the right spot for people going to the game, this was the spot of dead center field since home plate, when the park opened, was in the southwest corner, and the Pioneer Press said that this “left the crowd a very long block to walk to the entrance of the grounds.”

Lexington Park served as the home of the Saints until Comiskey moved the team to Chicago after the 1899 season. After a year without professional baseball, St. Paul got a team in the Western League in 1901 and then as a charter member of the American Association the following year. George Lennon was finding the location of Lexington Park to be too remote, though, and had a new park built in downtown St. Paul. Sunday games were played at Lexington Park, but from 1903 to 1909, the downtown site served as the primary home of the Saints. Starting in 1910, the Saints played full time at Lexington Park.

Lexington Park had already had a serious fire, in October of 1908, but an even greater one occurred following the 1915 season. The fire, which destroyed the grandstand, was discovered at 11 p.m. on Saturday night, November 14 by night watchman Emil Bossard. When the park was rebuilt, Bossard served as its groundskeeper for nearly 20 years before taking a similar job with the Cleveland Indians and becoming the patriarch of a groundskeeping family, causing the name Bossard to be synonymous with well-groomed fields in baseball. (Bossard had a later experience with fire, one more harrowing. On December 20, 1970, a fire at the Pioneer Hotel in Tucson, Arizona, killed 29 people. Bossard, however, survived, by climbing out the window of his room on the 11th floor and clutching the window sill until he was rescued.)

The rebuilding of Lexington Park following the 1915 fire included a reconfiguration of the playing field. The diamond was turned 90 degrees, moving home plate from the southwest toward the northwest corner of the lot. “The principle reason for the radical change in the arrangement is that it will prove a great convenience for the fans,” explained the St. Paul Pioneer Press on November 28, 1915. “The new plan would bring the fans into the grand stand almost as soon as they went through the gates, and the bleacherites would have less than half a block to walk. Under the present arrangement grand stand patrons have to walk the distance of two long blocks before they reach their seats in the grand stand, and the bleacherites have about the same distance to cover, and sometimes when rain has interrupted the game the fans have had a long run before they could reach the streetcars.”

The plan called for Lexington Park to be set back 100 feet from University Avenue, which was on the north side of the ball park, and 100 feet back from Lexington Avenue to the east. The main entrance to the grounds was behind home plate, at the corner of University Avenue and Dunlap Street.

Anderson and Kimball, in their Minnesota History article, wrote that the new Lexington Park emphasized function, unlike the recent remodeling of Nicollet Park. “The park was often described as a baseball plant. The deliberate and repeated use of this industrial term reminded people that the ballpark was a business enterprise that sold a product. This terminology reflected the ballpark s utilitarian aesthetic, one that was reinforced with the addition of unadorned light towers and the later remodeling of the ticket office. More than Nicollet Park, Lexington Park s character and identity were derived from the functional elements of the facility s interior spaces. The task was to speed fans and more of them to their seats. Baseball in St. Paul was amusement for the masses, without the elite imagery sought by more established clubs, including the Millers and many major league teams.”

With the new configuration, Lexington Park had familiar landmarks outside the stadium. The most prominent was the Coliseum Pavilion beyond the left-field fence, its roof being the landing site for many home runs. To the south, behind right field, was Keys Well Drilling, which erected a sign bearing the company name that, although outside the ballpark, was clearly visible to those inside.

This sign wasn t hit by home runs with the frequency of the Coliseum roof (if a ball ever hit it). In fact, for most of the life of the rebuilt Lexington Park, few balls cleared the right-field fence. The distance down the foul line in right field was 365 feet. A 12-foot-high wooden fence sat atop an embankment that led up to the fence.

Home runs to right field at Lexington Park were so rare as to be memorable. When the New York Yankees came to St. Paul for an exhibition game in June of 1926, the St. Paul Pioneer Press reported that only nine home runs had been hit over the right-field fence since the park had been rebuilt before the 1916 season. Bruno Haas was the only player to have twice homered over the fence.

Just as Lexington Park could be a nightmare for a lefthanded hitter, Nicollet Park in Minneapolis produced the opposite effect. In 1933, Joe Hauser of the Minneapolis Millers set a professional record with 69 home runs, breaking his own record of 63. Hauser was clearly helped by the friendly dimensions of Nicollet Park in Minneapolis, where he hit 50 of his home runs that season. However, it was at Lexington Park, on Labor Day that Hauser equaled and surpassed his own mark, hitting his 63rd and 64th home runs of the season and becoming the first player to hit two home runs to right field in the same game since the park was rebuilt.

In 1950 Lou Limmer of the Saints, a lefthanded hitter, led the American Association in home runs, even though he hit only one at home. Limmer s only season with the Saints was 1950. By the following year, he was with the Philadelphia Athletics of the American League. Thus he missed out on the shortening of the distance to right field, which took place during the 1951 season.

Disaster struck the Twin Cities on Friday, July 20, 1951 as high winds and floods caused millions of dollars in damage. One of the casualties of the gale was the right-field fence at Lexington Park, torn apart by winds reported to have reached 100 miles per hour. The Saints were in Kansas City at the time, giving management a chance to rebuild the barrier before the team returned.

By August, when the Saints were back from their road trip, Lexington Park had a new right-field fence, and this one was much closer to home plate. The distance down the line had been shortened to 330 feet. To make it a bit more challenging, a double-decked fence was erected that was 25 feet high, although the embankment that the previous fence had rested atop was gone.

What Came Next

The Millers had been looking at other sites since the 1940s. In June of 1948, the Millers, representing the parent New York Giants, and Minneapolis Board of Park Commissioners agreed on a 17-acre tract near Theodore Wirth Park, slightly less than three miles west of downtown Minneapolis, for a new ball park. The site was bounded on the north by Olson Memorial Highway, on the south by Glenwood Avenue, on the west by Xerxes Avenue North, and on the east by the Great Northern railroad tracks. It was the intention of the Millers/Giants to purchase the property, re-divert a stream to its natural channel, and construct a stadium with a seating capacity between 20,000 and 30,000. Home plate would be in the southwest corner, near the corner of Glenwood and Xerxes.

According to Halsey Hall in the Minneapolis Tribune of Thursday, June 10, 1948, Minneapolis Mayor Hubert Humphrey “said flatly that the stadium would be a good thing for clean professional sport, for recreation and for a growing place for young America in Minneapolis. He stressed the need for action and quickly.”

However, the first action came from residents in the Glenwood-Wirth area who objected to the site and quickly formed a committee to circulate a petition that read, “This group goes on record unanimously in requesting the park commissioners not to take the contemplated action in establishing a ball park in the Wirth park area, nor to sell, transfer, or lease the property to a commercial enterprise.”

Alternate sites were studied, and, in late 1949, the Minneapolis Baseball and Athletic Association went further west, beyond the Minneapolis city limits into St. Louis Park, and purchased 33 acres of land with approximately 1,400 feet of frontage on the south side of Wayzata Boulevard (now Interstate 394), about a quarter-mile west of what is now Minn. Hwy. 100. Preliminary architectural work began for a stadium for the site, but the land remained dormant as the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 brought about a moratorium on the construction of sports facilities.

Later in the 1950s, the New York Giants considered moving the team to Minnesota before instead moving to San Francisco. The organization continued to own the property, which was developed with such structures as the Cooper Theater, and for many years the lot was known as “Candlestick Park,” the same name as the stadium the Giants opened in San Francisco in 1960.

Even had the Giants moved to Minnesota, it is doubtful that they would have built a stadium on the St. Louis Park site at this time since both the Millers and Saints had new stadiums, both of which were designed with the intention of someday serving a major league team.

A bond drive led by local business interests known as the Minneapolis Minutemen began to finance construction a stadium for the Millers in suburban Bloomington, and the groundbreaking took place in June of 1955. The Millers played their final game at Nicollet Park in September of that year and moved into the new facility, which became known as Metropolitan Stadium, the following spring.

Nicollet Park was by this time owned by Northwestern National Bank (now Wells Fargo), which had purchased the property from the Carpenter family in November of 1951 for $145,000. The Millers still held a lease that ran through November of 1958; following the final game at Nicollet Park in September 1955, however, the ball park was torn down, and the bank relocated its Lake Street branch onto the abandoned site, where it remains today. In August of 1983, a historical marker, financed by donations of former Millers players and fans as well as by the bank, was unveiled in front of the bank, in what was right-center field of Nicollet Park.

Midway Stadium

Instead, a gravel-pit site to the southeast of the fair grounds was selected. Below the grade of surrounding areas, the stadium site was on the east side of Snelling Avenue and was bounded on the north and south by railroad tracks. Like the new stadium in Bloomington, the St. Paul facility was not confined by city blocks and had a parking lot outside the stadium.

Brooklyn Dodgers president Walter O’Malley came to St. Paul for the groundbreaking in April of 1956. One year later, on Thursday, April 25, 1957, Midway Stadium opened with a day-night doubleheader, the Wichita Braves beating the Saints in both games.

The distances down the line to both left and right field were 320 feet and 410 feet to center, and the outfield fence was 18 feet high. Joe Koppe of Wichita was the first player to clear the fence with a seventh-inning home run in the first game, before a crowd of 10,169, slightly below capacity. Another 5,800 fans showed up for the second game that night.

A road was squeezed in between the stadium and the Great Northern railroad tracks on the south, but there were problems with traffic jams, and access to Midway Stadium remained a problem throughout the life of the ball park.

The stadium had a single deck, but it was designed to provide for additional decks if needed to provide the necessary additional seating for major league baseball. “It will be very easy to expand this park to seat from 30 to 40,000 fans,” St. Paul city architect Alfred Schroeder told St. Paul Pioneer Press reporter Bob Schabert. “We could go up either one or two levels, depending upon the number of seats we need. Before we put on another level, however, we would probably extend the present grandstands all the way out to the fences.”

Saints president Mel Jones had already touted the new stadium in the March 1957 issue of ACE magazine, calling Midway “a structure well worth seeing and talking about.” Jones noted the large entrances and wide concourse area, which “leads you to any one of eight, extra-wide ramps extending into the Stadium proper.” The seats were color coded to match the ticket color: green for the box seat near the field, grayish white for the loge seats (which Jones called an “upper level box seat”), red for reserved seats, and blue for general admission. “Even a trip through the public rest rooms proves inviting,” wrote Jones. “Completely tiled with face brick tiling from top to bottom, they offer the finest in comfort and sanitation.”

The city of St. Paul made it clear that they wanted Midway Stadium to eventually host a major league team. Even though Metropolitan Stadium was not in Minneapolis, it was not acceptable to St. Paul interests. As early as July 1954, the city s mayor, Joseph Dillon, said that “under no circumstances” would St. Paul support the Bloomington site that was then under consideration and eventually chosen.

In August of 1959, barely a week after the news that Minneapolis-St. Paul would get a team in the Continental League (the proposed third major league), a group of St. Paul fans began a petition stating they would not support major league baseball unless 50 percent of the games were played at Midway Stadium.

No major league games were ever played at Midway Stadium. When the Twins came to Minnesota to begin the 1961 season, they played at Metropolitan Stadium. The arrival of the Twins also meant the departure of the Minneapolis Millers and St. Paul Saints. Midway Stadium had lost its primary tenant and missed out on the one it hoped to get.

For the next 20 years, the stadium was used for a variety of activities high-school and other amateur sports, exhibitions such as famed softball pitcher Eddie Feigner with the King and His Court, a practice facility for the Minnesota Vikings football team, wrestling. However, Midway Stadium became a drain on the city and was frequently referred to as a “white elephant.” It was demolished in 1981 as a new energy-park development took shape between Snelling Avenue and Lexington Avenue to the east.

A new stadium, smaller and less elaborate than Midway Stadium, was built on the other side of Snelling Avenue and later became home to a new St. Paul Saints professional team in 1993. Originally known as Municipal Stadium, it was later renamed to Midway Stadium.

The original Midway Stadium site has no vestige of its baseball history. As for the Lexington Park site, it was replaced by a Red Owl grocery store. In 1958 Red Owl imbedded a plague in the floor of the store to mark the site of home plate for Lexington Park (even though it was not the exact spot). Red Owl eventually moved out, but the property remained a supermarket. In the course of changing management, however, the home-plate plaque disappeared. In the summer of 1994, the Halsey Hall Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research began raising money from former Saints players and fans to erect another marker. In April of 1994 a new plaque was mounted on the outside of the structure. This building was later demolished, and in 2006 the marker was installed on a TCF Bank, a reminder to the rich baseball heritage of the site.

Copyright 2004 Stew Thornley

Minneapolis Millers Yearly Standings

Perry Werden’s Home Runs for the Millers, 1894-1896

Minnesota’s First Major League Baseball Team

Minnesota’s First Major League Baseball Game

The Beginning and End of Nicollet Park

Night Baseball in the Twin Cities

Millers Rivalry with St. Paul Saints

Protested Games Involving the Millers

Millers vs. Havana in 1959 Junior World Series

The Legend of Andy Oyler’s Two-foot Home Run

In 1889, the Minneapolis Millers moved into Athletic Park, a bandbox at the corner of Sixth Street and First Avenue North, behind the West Hotel in downtown Minneapolis. Estimates are that the distances down the foul lines were barely 250 feet, creating some high home run totals even in this era of the dead ball. So small was the park that players had to frequently “leg out” base hits to right field, and it wasn’t uncommon for a runner to be thrown out at first base on an apparent single to right.

In 1889, the Minneapolis Millers moved into Athletic Park, a bandbox at the corner of Sixth Street and First Avenue North, behind the West Hotel in downtown Minneapolis. Estimates are that the distances down the foul lines were barely 250 feet, creating some high home run totals even in this era of the dead ball. So small was the park that players had to frequently “leg out” base hits to right field, and it wasn’t uncommon for a runner to be thrown out at first base on an apparent single to right.

In early April of 1884, the St. Paul Base Ball Club began practicing for the upcoming Northwestern League season on grounds across the Mississippi River from downtown St. Paul (an area known as the city’s West Side even though it was actually south of downtown). As far as a location for their ball park, nothing had yet been decided. No one felt rushed to pick a location. After all, the team’s home opener wasn’t until June 9.

A new minor league, the Western League, was formed in 1894. It was a league whose president, Ban Johnson, hoped would eventually become a major league. Minneapolis was a charter member in 1894 but St. Paul didn’t get a team until the next year. The Sioux City franchise was dropped from the league, and a new team, in St. Paul, was granted to Charles Comiskey, one of the greatest first basemen of his time who finally retired as an active player and decided to try his hand at ownership.

To solve the problem of games on Sunday, Comiskey also rented a park on State Street, across the Mississippi River from downtown St. Paul, for future Sunday games. St. Paul’s team in the Western Association and in a previous Western League had played here from 1888 to 1892, even though a rising river sometimes left the ballpark under water. By the time Comiskey moved in, it was called State Street Park and served as the Sunday home for the Saints through 1896.

That park was Lexington Park, which lasted them 60 years, but there was another ballpark, in the early part of the 20th century that became a key part of the Saints’ heritage. Known as the “Pillbox” and sometimes referred to merely as the “Downtown Ball Park,” this short-lived park popped up in the shadow of the emerging state capitol. By this time, the St. Paul team was playing in a new minor league called the American Association. Lexington Park was its primary home, but George Lennon, the owner of the Saints, wanted a more centrally located park. In late 1902, Lennon announced plans for a new park between Robert, Minnesota, 12th, and 13th streets. Work began in early May of 1903, and the first game was played on Monday, July 20, with the Saints beating Minneapolis, 11-2, before more than 4,500 people.

The State Street Ballpark, underwater during spring floods in around 1890.

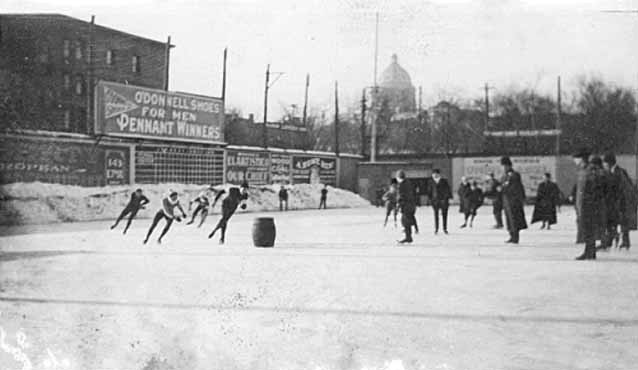

The Dale and Aurora (above) and Downtown (below) ball parks, both being used for ice events. Curling is taking place at the Dale and Aurora Park, in conjunction with the St. Paul Winter Carnival. At the Downtown Park, where the new capitol is visible in the background, is speedskating.

In 1896, Nicollet Park replaced a tiny ball park in downtown Minneapolis, Athletic Park, and represented a move outside the core area of the city. The location was picked, in part, because of its proximity to public transit, just off the corner of Nicollet Avenue and Lake Street in south Minneapolis.

In 1896, Nicollet Park replaced a tiny ball park in downtown Minneapolis, Athletic Park, and represented a move outside the core area of the city. The location was picked, in part, because of its proximity to public transit, just off the corner of Nicollet Avenue and Lake Street in south Minneapolis.

Stories of Nicollet Park’s quirkiness abound, their veracity at times dubious. Some of the tales revolve around the characters who inhabited the ball park. One was Bill Veeck, who owned the Milwaukee Brewers during World War II and became friends with Millers owner Mike Kelley. In his book, The Hustler’s Handbook, Veeck tells of some of the challenges of dealing with Kelley, including the problems that resulted from Kelley s Dalmatian, who sat with his owner in the front row of the right-field seats during games. Veeck claims that his Brewers once lost a game when the Millers with two out in the last of the ninth on a base hit to right field, near where Kelley and the Dalmatian sat. As Milwaukee right fielder Hal Peck attempted to field the ball, the dog “came flying over the railing to bite Peck right in the leg.” The dog continued to threaten Peck as he attempted to pick up the ball. As a result, two runs scored on the play, winning the game for the Millers. However, in all the games that Milwaukee played at Nicollet Park during the time Veeck owned the Brewers, there was never a game that ended in such a fashion. Thus, this story enters the ranks of legendary, but mythical, tales told about Nicollet Park and by Bill Veeck.

Stories of Nicollet Park’s quirkiness abound, their veracity at times dubious. Some of the tales revolve around the characters who inhabited the ball park. One was Bill Veeck, who owned the Milwaukee Brewers during World War II and became friends with Millers owner Mike Kelley. In his book, The Hustler’s Handbook, Veeck tells of some of the challenges of dealing with Kelley, including the problems that resulted from Kelley s Dalmatian, who sat with his owner in the front row of the right-field seats during games. Veeck claims that his Brewers once lost a game when the Millers with two out in the last of the ninth on a base hit to right field, near where Kelley and the Dalmatian sat. As Milwaukee right fielder Hal Peck attempted to field the ball, the dog “came flying over the railing to bite Peck right in the leg.” The dog continued to threaten Peck as he attempted to pick up the ball. As a result, two runs scored on the play, winning the game for the Millers. However, in all the games that Milwaukee played at Nicollet Park during the time Veeck owned the Brewers, there was never a game that ended in such a fashion. Thus, this story enters the ranks of legendary, but mythical, tales told about Nicollet Park and by Bill Veeck.

Lexington Park, like its counterpart in Minneapolis, was well removed from the center city when it opened in 1897. It was built by Edward B. Smith, who operated a St. Paul real estate company (and had been a part-owner of a National League team in Buffalo in the 1880s), for Charles Comiskey. Smith leased the ball park to the Saints until 1910, when he sold it to then-owner George Lennon for $75,000.

Lexington and Nicollet parks served the area well during the years it had minor league baseball and through a period when streetcars were a dominant form of transportation in the Twin Cities. Both phenomena were coming to an end in the early 1950s, however. Streetcar tracks were being torn out by the middle of the decade, and automobiles took over as the number-one way to get around in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

Not wanting to be left behind it the drive for major league baseball, the city of St. Paul also explored stadium sites and included $2 million as part of a $39-million bond issue for municipal improvements. Several sites were considered, including one by the State Fair grounds, but complications developed in procuring land from the University of Minnesota.