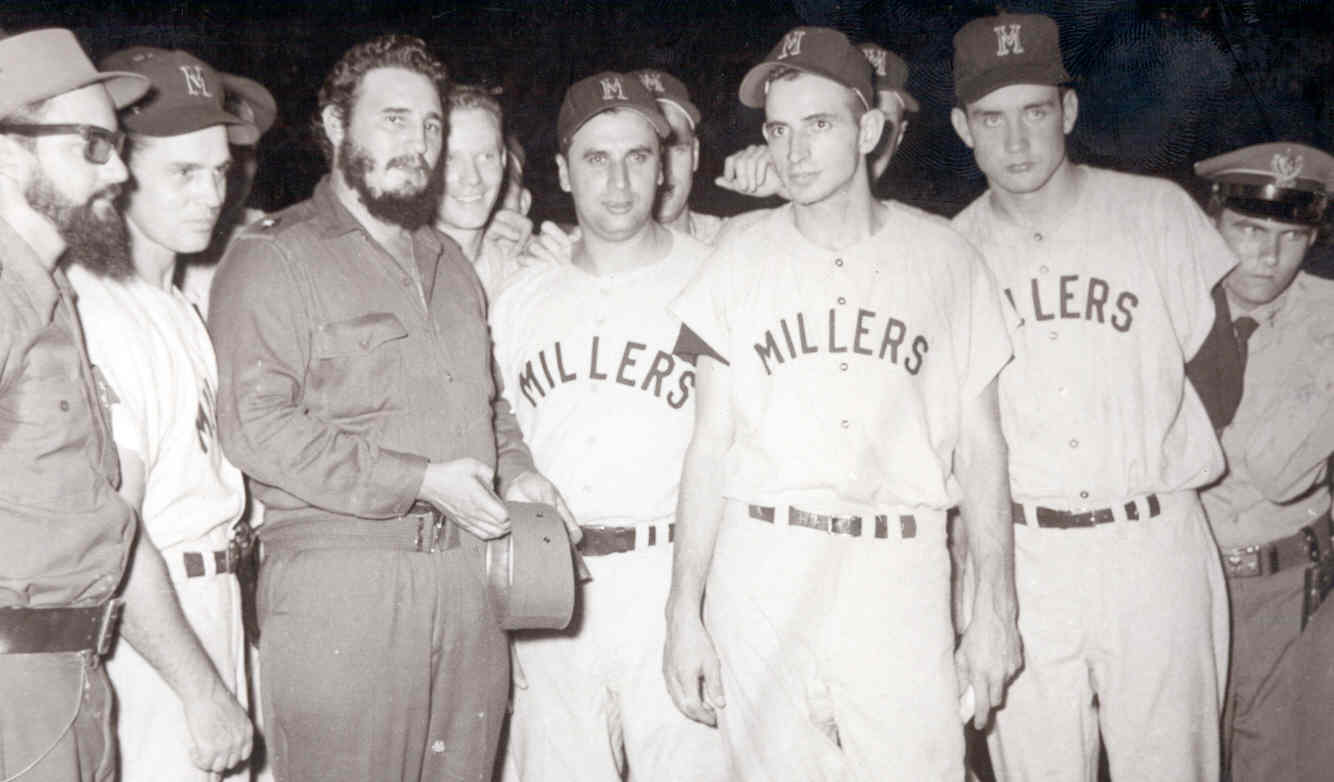

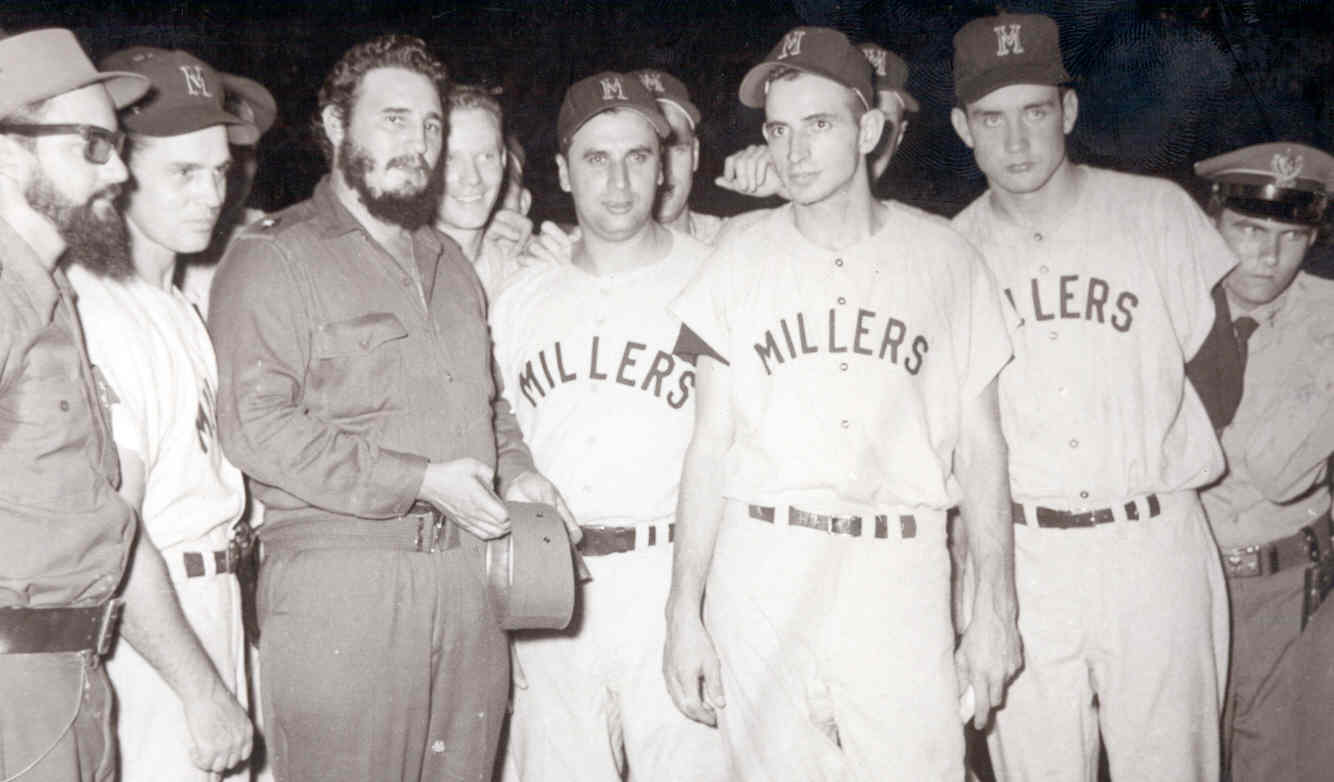

Fidel Castro (third from left) with Gene Mauch (second from left) and other members of

the Minneapolis Millers (to Castro’s left are Vito Valentinetti, Lu Clinton, and Tracy Stallard).

Minneapolis Millers

1959 Junior World Series vs. Havana

Fidel Castro (third from left) with Gene Mauch (second from left) and other members of

the Minneapolis Millers (to Castro’s left are Vito Valentinetti, Lu Clinton, and Tracy Stallard).

By Stew Thornley

Author of On to Nicollet: The Glory and Fame of the Minneapolis Millers

It was a minor league series with major league drama.

The Junior World Series, a post-season meeting between the champions of the American Association and International League that was played off and on from the early 1900s into the 1970s, produced its share of highlights and strange events.

But few Junior Series were more exciting—and none more bizarre—than the 1959 affair between the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association and the International League’s Havana Sugar Kings.

Not only were two contests, including the decisive seventh game, decided in the last of the ninth inning and another two in extra innings, but it was the only Junior Series in which the submachine guns outnumbered the bats.

The Millers, a Boston Red Sox farm team managed by Gene Mauch, were the defending Junior World Series champions, and were making their third appearance in the minor-league classic in the last five years. Minneapolis was bolstered by the recent addition of a young second baseman named Carl Yastrzemski, who had joined the team during the Association playoffs.

Havana, on the other hand, had finished the previous season at the bottom of the International League standings. In 1959, though, they rose to third during the regular season and then upset Columbus and Richmond in the playoffs for a berth in the Junior Series.

Managed by Preston Gomez, the Sugar Kings roster was comprised of a mixture of Latin and American players, several of whom would go on to respectable careers in the major leagues, including pitchers Mike Cuellar and Luis Arroyo and infielders Leo Cardenas, Elio Chacon, and Cookie Rojas.

Cuba in 1959 was no longer a Caribbean paradise. The recent years of revolutions and upheavals had turned the country into a battle-scarred island. Even the baseball diamond was not immune from the increased tensions following the overthrow of dictator Fulgencio Batista at the beginning of the year.

Shortly after midnight the morning of July 26, while the Sugar Kings and Rochester Red Wings were in the 11th inning of a game at Gran Stadium, demonstrations began in the streets of Havana, marking the anniversary of the 1953 attack on the Moncada army garrison in Santiago de Cuba by a band of rebels led by Fidel Castro, an event viewed as the conception of the eventual revolution.

During the course of the this observance, a wild burst of gunfire broke out, and a pair of stray bullets found their way inside the ball park, striking Rochester’s Frank Verdi, who was coaching third at the time, and Havana shortstop Leo Cardenas.

Neither Verdi nor Cardenas was seriously injured, but the incident nearly ended professional baseball in Cuba. The Red Wings left the country immediately, refusing to play the final game of the series, and they and other International League teams expressed fear and reluctance at returning to Cuba.

But baseball in Havana survived, in part because of the efforts and intervention of Fidel Castro, who by this time was premier of Cuba, having taken control of the government after Batista had fled the country.

Castro was a great fan of the sport and had even pitched in an exhibition game at Gran Stadium only two nights before the shootings.

And while the political turmoil continued, it could not obliterate the fanatical baseball interest that peaked when the Sugar Kings reached the Junior World Series. “There is no more violence in Havana,” said team owner Bobby Maduro. “The fans have only baseball to think about now.”

The series opened at Metropolitan Stadium in Bloomington, Minnesota. The first three games were to be played in the Millers’ home park, but a premature blast of wintry weather brought an early close to their end of the series.

Only 2,486 fans showed up on Sunday, September 27 to watch Havana take the opener, 5-2, in a game played in a steady drizzle. Even though they were more than 1,500 miles from home, the Sugar Kings had the most vocal rooting section at the stadium. Cuban natives living in the Minneapolis area staked out spots in the box seats behind the Havana dugout. Equipped with maracas and Cuban flags, the fans cheered wildly, particularly during the Sugar Kings four-run rally in the third inning.

As the weather grew colder the next day, the attendance dwindled to 1,062 for Game Two. The Millers bats were hot, however, and they used the long ball to battle back from 2-0 and 5-2 deficits. Roy Smalley—the brother-in-law of manager of Gene Mauch (and the father of the Roy Smalley who later played in this same stadium for the Minnesota Twins)—connected for a two-run homer to tie the game in the second inning, and home runs by Lu Clinton and Red Robbins retied the game in the last of the eighth. When Ed Sadowski opened the Minneapolis ninth with another home run, the Millers had pulled out a 6-5 win.

The Havana players appeared more bothered by the frigid temperatures that they were by the Miller rallies. They consumed large quantities of hot coffee during the game, and a newspaper photo the next day showed a trio of Sugar Kings huddled around a fire they had built in a wastebasket in the dugout.

On September 29, the thermometer reading plummeted even further. When the rain drops began turning to snow crystals, not only was that evening’s game called off, but the decision was made by the minor-league commission to shift the balance of the series to Havana.

The weather in Cuba was more conducive to baseball, and the reception that both the Sugar Kings and Millers received from the Havana fans was equally warm.

Upon their arrival, the teams received a gala civic welcome that included a parade from the airport to city hall. “This is a national event,” proclaimed Bobby Maduro.

Fidel Castro concurred, and attended each of the games played at Gran Stadium, even calling off a meeting of Cuba’s cabinet so he and other high government officials could attend one of the contests.

As Castro made his entrances onto the field through the center-field gate, the fans chanted his name and waved white handkerchiefs, giving the appearance of a snowstorm despite the 90-degree temperatures. The premier sat in different sections of the stadium during the series, and at one point even found a spot on the Havana bench.

In a home plate ceremony preceding the first game played in Havana, Castro addressed the 25,000 fans in attendance: “I came here to see our team beat Minneapolis, not as premier but as just a baseball fan. I want to see our club win the Little World Series. After the triumph of the revolution, we should also win the Little World Series.”

The premier shook hands with the players from each team before settling into his box seat to watch the game.

The pomp at the plate, however, wasn’t enough to make the Millers forget the strife that surrounded them. Everywhere they went in the city—from their quarters at the Havana Hilton to the ball park—they were greeted by the sight of Castro’s bearded troopers.

Nearly 3,000 soldiers were at the stadium during the game, many lining the field and others stationing themselves in the dugouts, their rifles and bayonets clearly evident. “Young people not more than 14 or 15 years old were in the dugout with us, waving their guns around like toys,” recalled Millers pitcher Ted Bowsfield. “Every once in a while, we could hear shots being fired outside the stadium, and we never knew what was going on.”

Gene Mauch reports that the soldiers were not above trying to intimidate the Minneapolis players. As Miller centerfielder Tom Umphlett entered the dugout after making a catch to end an inning, a soldier made a slicing motion across his throat. Umphlett and the other players clearly understood the message.

“Our players were truly fearful of what might happen if we won,” said Mauch. “But we still tried our hardest, figuring we’d take our chances if we did win.”

The atmosphere, however, was still unnerving to the Millers. They couldn’t hold a 2-0 lead in Game Three as Havana scored two runs in the last of the eighth to tie it and another in the last of the tenth to win it.

Carl Yastrzemski, who hit a 400-foot home run in the game, said the Millers found no relief away from the stadium. “We had been warned not to leave the hotel between games,” he said in his autobiography, Yaz. “It was like a revolution in the streets, even though it wasn’t violent. But with the guns and the noise it was just scary.” The Minneapolis relief corps was unable to hold another late-inning lead in the fourth game. This time, Havana tied the game, 3-3, on a run-scoring single by Dan Morejon in the bottom of the ninth. Morejon then drove in the winning run with another single in the 11th and the Sugar Kings were within one game of the championship.

On the verge of extinction, though, the Millers battled back. Ignoring Castro’s troopers, they won the next two games to tie the series and force a seventh and deciding game.

At this point, Castro decided to get into the act. After entering the stadium prior to Game Seven, he made his way around the warning track to get to his box seat. According to the Millers’ Lefty Locklin, as Castro passed the Minneapolis bullpen, he paused, looked at the players, patted a large revolver on his hip, and said, “Tonight, we win.”

The Millers had other ideas, however. Joe Macko led off the fourth inning with a home run, and, when Lu Clinton did the same to start the sixth, Minneapolis was ahead, 2-0.

The lead held until the eighth when Elio Chacon opened the inning with a single. One out later, Dan Morejon nicked the right-field foul line with a ball that bounced into the stands for a ground-rule double. Ray Shearer looked at a called third strike for the second out, but pinch-hitter Larry Novak brought Castro and likely all of Havana to its feet with a single to center that brought in two runs to tie the score.

In the last of the ninth, Havana put runners at first and second with two out. The pesky Morejon then stepped to the plate and lined the first pitch into center field to bring in Raul Sanchez, who slid home ahead of Umphlett’s throw with the winning run.

The entire city celebrated the Sugar Kings’ Junior World Series championship. As for the Millers, they went home disappointed, but relieved. “In some ways,” recalls Ted Bowsfield, “nobody minded losing the game in that country and under those conditions.

“We were just happy to get it over and to get out of town with our hides.”

Copyright 1994 Stew Thornley

Minneapolis Millers Yearly Standings

Perry Werden’s Home Runs for the Millers, 1894-1896

Minnesota’s First Major League Baseball Team

Minnesota’s First Major League Baseball Game

The Beginning and End of Nicollet Park

Night Baseball in the Twin Cities

Millers Rivalry with St. Paul Saints

Protested Games Involving the Millers

The Legend of Andy Oyler’s Two-foot Home Run