We moved to southeast Minneapolis in the spring of 1965. My dad had grown up in various places in Southeast and had spent a lot of time attending Minnesota Gophers sports events. He wanted to pass the experience on to me, which wasn’t hard for a couple of reasons: one, he had a willing subject, and two, my mom was teaching at the University and, as a result, able to get faculty season tickets. At the time, these tickets covered all sporting events—football, basketball, hockey, track, and baseball.

My dad took me to my first Gophers baseball game in April of 1966. Frank Brousseau shut out Wisconsin, 2-0, in a nine-inning game that took only 1 hour, 30 minutes. The Gophers battled Ohio State that year for the Big Ten championship as well as for the only chance to advance toward the NCAA championship. On the final weekend of the Big Ten season, the Gophers played the Buckeyes in Columbus. Ohio State won the game and went on to win the Big Ten title as well as the NCAA championship (the last time a Big Ten team has won the NCAA tournament). The Gophers faced similar disappointment in 1967. Once again, they battled the Buckeyes for the top spot in the conference. This year, the meeting between the two clubs was again on the final weekend of the season (on a Friday with the season ending on Saturday); however, in 1967 the matchup was in Minnesota and it was also a doubleheader rather than a single game, as it had been in 1966. Since Minnesota trailed Ohio State in the standings, the Gophers needed to sweep the doubleheader. Minnesota won the first game, on a shutout by Jerry Wickman, but lost the seven-inning second game when the Buckeyes, trailing 2-1, exploded for eight runs in the sixth inning.

One of the Gophers’ top players in 1966 and 1967 was shortstop Bob Fenwick. Fenwick’s younger brother was bat boy for the Gophers. Fenwick signed a pro contract after the 1967 Big Ten season, meaning his brother wouldn’t be back and that there would be an opening for a bat boy.

I became bat boy for the Gophers summer league team, an entry in the four-team Metropolitan Collegiate League. Dick Siebert, the Gophers legendary coach, was the league commissioner. In the summer of 1967, Bill Haas coached the Minnesota team in the league. Bill thought I did a good job and said he would recommend to Siebert that I be the regular bat boy for the Gophers the following season. During the winter, I visited one of the Gophers indoor practices in the University Field House and talked to Siebert about becoming their bat boy.

I ended up serving as the Gophers bat boy in 1968 and 1969 as well as during the summer-league season in 1969. The Gophers won the Big Ten championship in both 1968 and 1969, the former title being won with a doubleheader sweep of Michigan State on the final day of the season. It was the most memorable day I have spent in baseball and one that I have written about elsewhere.

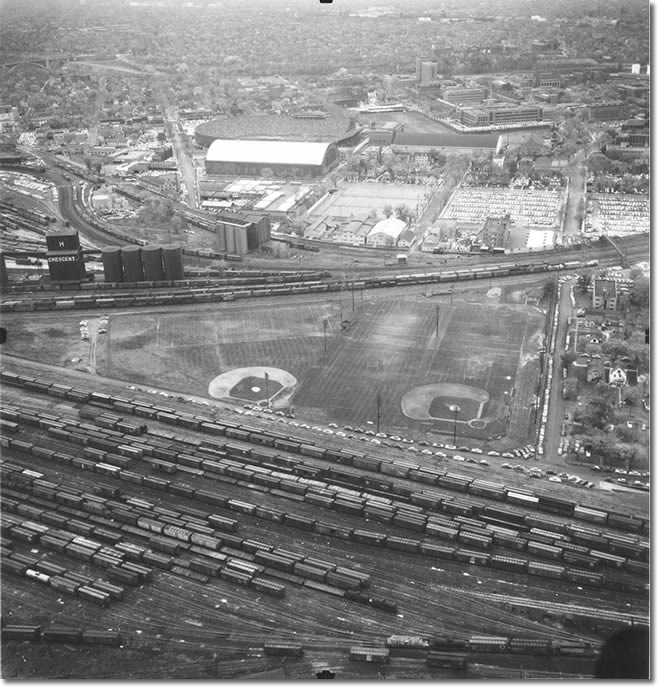

The writing that follows is thoughts and remembrances on other events and incidents on my time with the Gophers:The Gophers played at Delta Field when I started following them. It was renamed Bierman Field in 1968, a name that followed them to their new stadium, which opened next to the existing one in 1971. In 1979, the new stadium’s name was changed to Siebert Field, in honor of Dick Siebert, who had died the previous December. The area around Delta/Bierman Field was changing, as well. The blocks between 15th Avenue and the ballpark contained houses and apartment buildings. There was a footbridge that provided access across the railroad tracks to the rest of the campus (a bridge my dad and many other fans took when we walked to Memorial Stadium on football Saturdays).

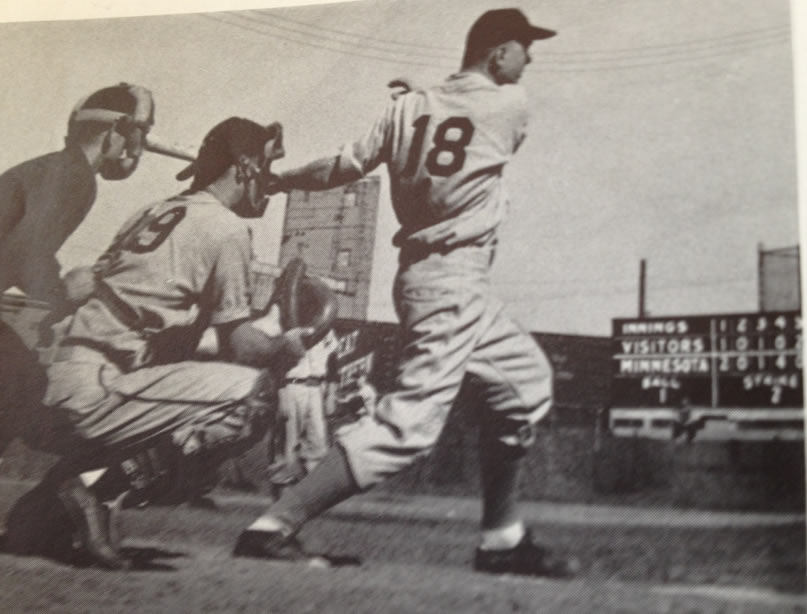

The footbridge remained at that spot until the 1990s (it even contained a sign with an arrow for Delta Field for many years after Delta Field was renamed and eventually abandoned), but the houses and apartment buildings were knocked out for more athletic facilities for the university—a track, a football practice field, and the Bierman Building, which housed the athletic offices (many of which used to be in Cooke Hall). The entrance to Delta Field was in the right-field corner. Home plate was toward 8th Street, and there was a gate there, as well. This gate was always opened after the game to allow people to leave. Often, someone staffed it before the game and would let in people with season tickets (as opposed to people who had to go to the main gate to purchase their tickets). The dugouts were wooden and covered with asphalt shingles. The backstop consisted of chicken wire strung between metal poles that were painted maroon. The bat racks were inside the dugouts although by 1968 the bat rack in the first-base dugout (the one used by the home team except for the post-season when, for whatever reason, it became the visitors’ dugout) was moved outside the dugout and attached to the backstop. The stands consisted of bleachers that, after the season, were moved to the end zone at Memorial Stadium. As for the scoreboard, it was a beauty (shown in the picture below). It was in the left-field corner and contained space for the inning-by-inning results. At the end of a half-inning, the operator put up the appropriate number. The ball, strike, and out indicators were on cylinders that contained numbers. The scoreboard operator sat on a stool between the ball and strike cylinders and twirled them to the proper number as the count changed. He would have to get up and walk over to the other cylinder when the outs changed. I had a chance to work the scoreboard at various times—in the summer of 1966, before I became bat boy, and during the summer league seasons when one could be called on to do just about anything (more about that later).

Players were still leaving their gloves on the field when I started following the Gophers. I believe the practice ended before I became bat boy, but I still have a vivid memory of seeing the infielders turn and hurl their gloves onto the outfield grass after the third out of an inning. There were few batting helmets, generally just one of each size between 6-7/8 and 7-5/8. Thus, players had to share helmets and did not wear them on the bases. The players would either fold their regular hat and stuff it in their back pocket when going to the plate, or they would fit their regular hat inside the batting helmet before putting it on. If a batter reached base, I would have to, after picking up the bat, run out and catch the helmet as it was thrown to me by the runner or the coach. Catching a batting helmet, especially when you are already holding a bat, is not an easy thing to do. Often the edge of the helmet or visor was sharp and could cause a cut on the hands if caught wrong. It was also easy to jam a finger or thumb trying to catch a helmet. What was fun, however, was having a pitcher reach base. That’s because I would be holding his jacket while he was at bat and would have to run it out to him if he got on. If he made it to second, that was really great, since I got to run all the way across the diamond to deliver his jacket.

A weighted bat (and eventually weighted batting donuts), a pine tar rag, and a rosin bag were things I had to bring out to the on-deck circle each inning (and bring back to the side of the dugout at the end of the inning). Handling these things, as well as the bats and helmets that became caked with pine tar and rosin over time, left me quite dirty at the end of the game. I also reeked of pine tar—not that that’s a bad smell. In fact, I grew to like it, and to this day, a whiff of pine tar is an aromatic scent as it brings back many happy memories of my days as Gophers bat boy.Dick Siebert was all business during a game. I showed up during a practice once, and he was completely different as he greeted me with a big smile. However, on game day, he was pretty quiet—sitting at the end of the dugout with the scorebook in his lap. Usually, there was little that could distract him from the game. Once, though, I found a way (unintentionally) to get his mind off baseball. I came to a game directly from school and brought my books—consisting of a Hardy Boys book and a couple of wrestling magazines—which I left on top of the dugout. Soon after, our student manager, Lightnin’ Gary James, noticed the books on top of the dugout and brought them in. “Are these yours?” he asked me, adding that he thought it would be best if they were not left on top of the dugout. Before he could give them to me, Siebert said, “Wait a minute. What’s this?” He took the books from Gary and said, “Hardy Boys? Wrestling magazine? Is this what they’re teaching you in school?” The other players got a kick out of it, and I enjoyed the exchange as well.

While it was unusual to have Siebert engage in that kind of banter during the game, I often got involved in joshing with some of the players before a game. Gary Petrich, one of the team’s top pitchers, was a favorite of mine. He was a great guy to kid around with. One time, we were joking about having a party after the game. “Sure, you can come,” he said to me. “Bring some beer and a girl.” I was at the age where most of my friends and I still thought girls were uncool, so I replied, “I’ll bring the beer, but I’m not going to bring a girl.” Gary replied with something to the effect of, “That’s the way,” leaving me with the impression that Gary also found girls uncool, causing my esteem for him to rise even higher. However, I later found out he had a girlfriend, shattering many of my illusions of Gary being a member of the “He-Man Woman Hater’s Club.”

Sometimes I could crack the players up without trying to. One Friday we had a long doubleheader with Indiana that was particularly rough on me. I was having problem catching the batting helmets thrown to me after someone reached base. I jammed my fingers a couple of times. By the end of the day, I was pretty tired and dirty, but I still headed over to my high school (junior high, for me) to go to the Mardi Gras festival they had that night. Before the doubleheader the next day, I was sitting with some of the players in the dugout when one of them commented about the rough time I had the day before. I added that I was so dirty that when I went to the festival at the high school, I had to “spend half the night spitting on my hands to get them clean.” The players thought that was the funniest thing, even asking who my comedy writer was. I’d been serious when I said it—after all, that’s how ballplayers cleaned themselves, wasn’t it?Sometimes the players seemed to take on an almost fatherly role and there was one incident that caused them both to laugh as well as to wonder where they had gone wrong in their raising of me. It occurred when I got in some trouble at school for throwing dictionaries out the window. It started when the teachers began using dictionaries to prop open the windows as the weather got nice (this being a city high school, it wasn’t like we had windows that operated properly). A few of us thought that, by staging a fight with some shoving, we could push someone against the dictionary and cause it to be bumped out the window while making the whole thing look like an accident. The ploy didn’t work very well. I got shoved backward but missed the dictionary and had to throw an elbow (two or three times, as I recall) to bump the dictionary out the window. Over the next couple weeks, for whatever reason, we continued the practice of jettisoning dictionaries, although we dispensed with the theatrics. Rather, when the teacher had her back turned, we’d toss a dictionary through the open window, which was being propped open by another dictionary. In addition to this causing a shortage on dictionaries, it started raising complaints from other teachers who had their cars parked in the lot beneath the windows and were coming out to find dents on their hoods, trunks, and/or roofs, accompanied by a dictionary.

One day a handful of us got called to the office and had to go in, individually, to talk to the vice-principal, Mr. Satter. Before starting school at Marshall High, I had heard horror stories about what a mean man Mr. Satter was, but he turned out to be quite nice and gentle. He gave me a lecture regarding the inadvisability of throwing dictionaries out the window. When he was done, he said, “You will tell your parents, won’t you?”

“Is this guy for real?” I thought. “Is this a test? Will he pretend to trust me to tell my folks and then call them a week later?” I wasn’t sure what to make of it all, but I replied to his question, “Oh, yes. I’ll tell my dad as soon as I get home.” (Of course, I never did, and it wasn’t a test; Mr Satter never called him, either.)

Before leaving, I thought I might as well get Mr. Satter to okay the note I had from my dad, excusing my from school early on the coming Friday for a Gophers game. After Mr. Satter read the note, he got very excited, so much so that he never bothered to listen to any of my answers to his questions.

“Bat boy for the Gophers!” he said. “That’s great! How did you get to be bat boy?”

“Well,” I started to reply. “I went and talked to Dick Siebert and he . . .”

“Wow. That’s really great. Did you see the Twins game last night?”

“I was out collecting for my paper route, but when I got home I was able . . .”

“Wasn’t that argument with Duke Sims something? Do you think he deserved to be kicked out?”

“Well, I didn’t see that part, but I heard . . . ”

“My goodness. Bat boy for the Gophers. I’ll bet none of the Gophers ever threw dictionaries out the window.”

“I’ll be sure to ask them about that, sir.”

And I did. That Friday, before the doubleheader, I sat in on a conversation with some of the players and finally asked if any of them had ever thrown a dictionary out a school window. Of course, they wondered why in the world I would ask such a question and asked me to explain. When I did, they found it all pretty funny, but, as I said, they wondered if they had better start imposing more discipline on their bat boy.My duties as bat boy including running after balls that were fouled off into the backstop behind the plate. I’d either toss them back to the umpire right then or take them back to the edge of the dugout, where the master supply of balls was kept. When the umpire needed more balls, he’d let me know, and I’d either run some out to him or toss them to him. Usually, I tossed them, but, at least for a while, it could hardly be called a toss. I was throwing the balls overhand, sometimes a bit too hard, to the umpire, who caught them barehanded. I never noticed anything amiss, but my dad—who attended most of the games—finally told me to let up on the throws. He said that the umpires were sometimes shaking their smarting hand after catching one of my tosses. It had even gotten to the point that other fans were laughing at the umpire’s distress after taking a throw from me, but I was oblivious to the whole thing.

I enjoyed running out to get the balls that were fouled back into the backstop. For a while, one of my good friends, Rich Stahnke, was serving as the regular bat boy for the visiting team. Rich and I liked to compete against one another to see who could get to the ball first. It was an advantage for the bat boy whose team was at bat at the time, since the bat boy would then be stationed outside the dugout instead of sitting inside it. But that didn’t stop the other bat boy from going after the ball. When a ball was fouled back, we both tear after it as fast as we could, sometimes diving for the ball. The fans seemed to enjoy our antics, although we were both very careful to do what we had to do as quickly as possible and then to get back to our positions. We knew we’d hear about it if we delayed the game.

I had a different situation with a different bat boy, though, in the District 4 playoffs in 1968. It was a losers’ bracket game between the Gophers and the Ohio University Bobcats. Ohio U. had a smarmy bat boy whom I took a dislike to. Rather than run out to pick up a bat (something my dad once barked at me for not doing; “You have to hustle when you’re on the field,” he told me), the Ohio bat boy sort of strutted out to get it. He didn’t hustle on the field. Midway though the game, I decided to show the slacker a good example of hustle when a pitch was fouled back. Ohio was at bat, which meant that I was in the first-base dugout and a lot farther away from the ball than the slacker (especially since it was hit closer to the Ohio dugout). However, I took off from the dugout as soon as the ball was fouled off while the slacker did his usual saunter toward the ball. As a result, I got to it almost as quickly as he did. The slacker was just bending over to pick up the ball when I dived for it. We grabbed it at the same time and started tugging. Wanting to take care of the matter without delaying the game, I yanked the ball out of his hands and started to get up so I could toss it to the umpire and get back to the dugout. But next thing I knew, the slacker had a headlock on me. I gave him a shove, just like I’d seen it done many times on All-Star Wrestling, and clenched a fist in case the slacker came back at me. He didn’t, though. He just kept running back toward the Ohio dugout (at least I finally got the guy to hustle on the field). So, there I was, on my knees with a clenched fist, feeling a little foolish, and wondering if I was going to be in trouble for holding up the game. But as I got up, I saw the umpire, the batter, and players on the field staring at me with big grins. They enjoyed the whole show. I found out that the crowd did, too, since they cheered me as I ran back to the Gophers dugout. The players inside the dugout also found the whole thing to be pretty funny, and they razzed me a bit (“Gee, Stew, why didn’t you slug that guy?”) when I got back. Never mind that this was an important playoff game; all involved still seemed to see the humor in a tussle between bat boys.

I may have won the battle with the slacker on the field, but, unfortunately, he got the last laugh as his team won the war. Ohio came back with three runs in the last of the ninth to beat Minnesota and eliminate the Gophers from the playoffs.The 1968 playoffs had a disappointing ending, but they also featured some exciting games. The tournament opened on a Thursday at Bierman Field. The Gophers were the visiting team in their first game, against Valparaiso. Valparaiso took a one-run lead into the top of the ninth, but the Gophers had a runner on third (Bob Fisher, a speedy pitcher who was in as a pinch-runner) with Marv Menken at bat. There were two out. It looked like it was up to Menken to get a hit to bring in the tying run. Instead, Fisher stole home. Stationed outside the first-base dugout, I had a great view of the play as Fisher raced toward the plate as the pitch came in. Fisher slid as the catcher took the pitch and dove forward with the tag. From my vantage point, I could clearly see that Fisher had gotten in under the tag. But I realized that the umpire had a different view and might not have seen it the same way. It seemed like time stood still as we awaited the call. But then the umpire threw his arms out to signal safe. Watching someone attempt a steal of home with his team down by a run with two out in the ninth, and then do it successfully to tie the game, remains one of the most exciting baseball plays. Fisher wasn’t done. He took the mound in the last of the ninth and ended up being the winning pitcher as the Gophers won in 11 innings.

The Gophers next faced the Southern Illinois Salukis, a fine team led by Jerry Bond, their speedy sophomore centerfielder and leadoff batter, and Mike Rogodzinski, who went on to play with the Philadelphia Phillies a few years later. The Friday games were scheduled for Midway Stadium in St. Paul, but rain washed all that out. The tournament resumed on Saturday, at Bierman Field. In addition to the matchup between the Gophers and Salukis, there was other excitement. That morning, a new poll was released that ranked the Gophers as the number-one team in the nation. Inside the Gophers locker room—a small concrete-block structure beyond the right-field corner—a large “1” had been put up with white tape. The game was a wild one. Southern Illinois scored four runs in the top of the first, but the Gophers battled back. Minnesota eventually took the lead, but Southern Illinois came back and ended up winning the game, 10-9. It was a deflating loss. What I remember most was the silence back in the locker room. The only sounds were the scraping of spikes on the concrete floor. Someone finally went to the blackboard and, in disgust, ripped off the tape that had made the “1.” An outline of the 1 remained, but someone else soon came by and rubbed off the remaining vestige of the summit the Gophers had occupied at the start of the day. (More than ten years later, when the locker room had been transformed into a headquarters building for intra-mural sports at the university, I walked into the building before a softball game. I was wearing spikes and the sound of those spikes on concrete took me right back to that depressing scene after the Gophers loss to the Salukis.) Losing to Southern Illinois meant the Gophers had to come back through the losers’ bracket. A win in the next game would put them in the championship round, against Southern Illinois, in a situation in which the Gophers would have to win two games and the Salukis only one to win the tournament and advance to the College World Series. Knocking off Southern Illinois twice in a day wouldn’t be easy, but it didn’t matter anyway, since the Gophers lost their next game (the one against Ohio University in which I got in the tussle with the opposing batboy) and were eliminated from the tournament.

In 1969, the Gophers won the Big Ten title again—this time in much less dramatic fashion—and again hosted the District 4 Tournament. In the first game, the Gophers beat Ohio University (the Bobcats no longer had their non-hustling bat boy but they did have a slugging shortstop named Mike Schmidt, who hit a two-run homer in the game. Schmidt went on to a major league career in which he hit 548 home runs). Southern Illinois was back in the tournament and demolished Ball State, 15-6, in the first game. The Salukis hit nine home runs in the game. The Gophers and Salukis met the next night in the winners’ bracket game, at Midway Stadium. There was a good crowd, which meant that the start of the game had to be delayed since most of the fans were stuck in their cars on Snelling Avenue, trying to get to the stadium.

Gary Petrich, my favorite, pitched for the Gophers. Petrich was 7-0 coming into the game. Minnesota got off to a 3-0 lead, but the Salukis chipped away at the lead and had closed the gap to 3- 2 when they came up in the last of the eighth. Petrich had kept Jerry Ball, their nemesis from the previous year, quiet up to that point. Petrich retired the first two batters in the eighth, bringing up Ball. He got Ball to feebly top the ball down the third-base line, so feebly, however, that the speedy Ball was able to reach first safely. Ball then went to third on a hit-and-run single by Rogodzinski and scored the tying run when Petrich uncorked a wild pitch..

The game stayed tied until the 11th, when Ball led off the bottom of the inning with a triple. The Gophers intentionally walked Mike Rogodzinski and Bill Stein (both future major leaguers) and pulled in the infield and outfield. Barry O’Sullivan then hit a fly ball to center was deep enough, despite a strong throw from Bob Nielsen, to bring in Bond and win the game for Southern Illinois. The Gophers then went out and played a flat game against Ball State, losing 4-1 and being eliminated from the tournament.That was the end of my days as bat boy for the Gophers during the regular season, although I was with their summer league team again in 1969. The summer league was laid-back and interesting in a number of ways. Roster sizes were smaller, and there weren’t, in general, as many people around to help out. This meant that everyone had to chip in to help out with various duties. Shagging foul balls—a task handled by members of the freshmen team during the regular season—was the worst, especially balls hit across 8th Street and onto the railroad tracks. Once I was off in pursuit of one such fugitive horsehide and was approaching the gate that provided access to 8th Street when another foul ball sailed up and back. It would have joined the other one by the railroad tracks, except that it went right into one of the lights. (Old Bierman Field did have some lights but they weren’t very powerful. They’d allow a game to extend into the hours when dusk was setting in, but weren’t bright enough to make much difference once it actually got dark). The foul ball shattered the light, sending a shower of glass down onto the pavement right in front of the gate, a spot I would have been in had I been a few steps faster.

Often, I got to engage in activities a little more fun—or, at least, not as unfun—than shagging fouls. These included going out to the left-field corner to operate the scoreboard, warming up one of the outfielders between innings, or keeping the scorebook. (I kept the scorebook in lieu of the other choice I had at the time—going down to the bullpen and warming up a relief pitcher.)

It was at a summer league game in late August that I picked up my last bat. Jim Wallace, an incoming freshman, was at the plate, and I was outside the dugout, reflecting on the fact that this could be the last batter for me as bat boy. I was interrupted from my thoughts when Wallace fouled off a vicious liner, right at me. It hit me squarely in the right thigh. My last batter, and, for the first time, I was hit by a batted ball. What a way to end it all—limping out to pick up my final bat when Wallace grounded out right after that.Footnote

One of the things I enjoyed during and after the time I was bat boy for the Gophers was running into some of the people.Lu Gronseth became a student teacher in my gym class at Marshall-U High School after I was done being bat boy. In the early 1980s, I was umpiring a softball game that Chris Farni played in and had a nice chat with him after the game. Later in the 1980s, Jack Palmer joined Toastmasters, an organization I was in, and we got to know each other pretty well.

On September 27, 1986, I got to play in a Gophers alumni game, even though I had been only the bat boy for them. The teams included a couple of players who had been on the team when I was bat boy, Tom Epperly, who was on the other team, and Mike Walseth, who was on the same team as me. I got into the game in the middle innings and did nothing to distinguish or embarrass myself at second base. In my only at-bat, I grounded out to end the inning with runners on first and second. I was just happy to have made contact, especially since Bill Thompson, the pitcher I faced, had finished his career with the Gophers only the year before and could still “bring it.” However, the biggest thrill in the game came in the last of the seventh. The game was tied when Mike Walseth, the best hitter on the team when I was bat boy, homered over the right-field fence to win the game. As I jogged out to home plate with the rest of the team to greet him, I had to remind myself not to pick up the bat. This time it was someone else’s job.

A few years after that I met Roger Zahn when I was speaking at the Minnesota Entrepreneurs Club.

I got to know Pete Hepokoski the best. Pete had been the student manager in 1969, and in the early 1980s, I learned that he was in Toastmasters. By the time I connected with him, he was no longer in Toastmasters, but I was able to get him to join the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) and we became friends. Pete had the idea of having a reunion for the players on the 1968-1970 teams, all of them champions of the Big Ten, in 1994, the 25th anniversary of the middle year of those titles. We formed a committee that included Dave Cosgrove, one of the top pitchers on the team and a very nice and classy guy, and Al Kaminski.

The reunion took place during a tournament at the Metrodome in early March. We gathered in the football press box before a game between the Gophers and Arizona, which was coached by Jerry Kindall, who had been the assistant coach for the Gophers during that title run. Just prior to the game we went down to the field and were directed onto the diamond to be introduced. At that point, Kindall came out of the Arizona dugout to join us and went down the line, shaking hands with each of us. After the on-field ceremonies, our group went back to the football press box to watch the game and that night had a banquet. Jack Palmer was the master of ceremonies, and Kindall was the speaker.

Those at the reunion were Jay Youngquist, Phil Flodin, John Peterson, Tom Epperly, Pete Hepokoski, Russ Rolandson, Mike House, Brian Love, Bill Kendall, Scott Stein, Gary Morgan, Dave Cosgrove, Mike Walseth, Lightnin’ Gary James, Roger Zahn, Jack Palmer, Don Shellum, Al Kaminski, Scott Frantzen, Bob Schneitz, Greg Wasick, Chris Farni, Bob Michelletti, Bob Nielsen, Steve Chapman, Lu Gronseth, and Larry Carlson.

I talked to some of the players in 2004 in lining up a panel of former Gophers for our SABR chapter. Greg Wasick was the only one from that group who was able to make the panel, and I maintained some contact with him via e-mail. I saw Greg and a few other players from those years, including Bob Nielsen and Noel Jenke, at a Gophers game at the Metrodome a year or two later.

In 2008 the Gophers held a reunion weekend for the Big Ten champion teams from 1958, 1968, 1988, and 1998. They honored the 1968 team before the Saturday night game on March 8 with a pre-game reception in the suites in the right-field corner. Phil Flodin, Russ Rolandson, Brian Love, Ken Dagel, Dave Cosgrove, Mike Walseth, Roger Zahn, Jack Palmer, Al Kaminski, Marv Menken, Greg Wasick, Chris Farni, Bob Nielsen, Larry Carlson, and Gary Petrich were there.

It was the first time I had seen Gary Petrich since he had pitched for the Gophers, and I had a nice chat with him, among others. Gary now lives in Colorado, and he told me his son had googled his name and come upon this page with the story about the beer and the girls.

We were introduced on the field before the game, and John Anderson, the current coach, presented us each with a baseball that had “Big Ten, 1968 Champions” stamped on it.

A year later the Gophers had a reunion for the 1959 and 1969 Big Ten champion teams before a Saturday afternoon game against Northwestern. Dick Alford, Lee Brandt, Ron Causton, John Erickson, Wayne Haefner, Martin Nelson, James Norwick, and Jim Rantz were present from the 1959 team and Dave Cosgrove, Lu Gronseth, Chris Farni, Noel Jenke, Brian Love, Marv Menken, Bob Nielsen, Jack Palmer, and Mike Walseth from the 1969 team.

Another connection happened in 2012 at a meeting of official scorers at Major League Baseball in New York when I met Ron Roth for the first time. Ron has coached baseball at the University of Cincinnati and Archbishop Moeller High School in Cincinnati and has been the official scorer for Reds home games for more than 30 years. When I got home from the meeting Ron sent me an e-mail and told me he just learned that our paths had crossed before and that he was going to send me something. He aroused my curiosity, and the following week I got a letter from him. He had a note that said, after reading my bio that mentioned I was bat boy for the Gophers, he figured out that we were on the same baseball field together in 1968. He included the front page of the June 1, 1968 Minneapolis Tribune that had a picture of him peering out the dugout during a rain delay. The caption identified him and said he was the student manager of the Ohio University team. That was a great connection to find out about.

In 2017 Pete reminded me that the 50-year reunion of these teams was coming up. Pete was no longer living in the area, but he did a lot of the organizational work. Dave Cosgrove, Greg Wasick, Jack Palmer, Bob Micheletti, and Gregg Wong, who was the official scorer and public-address announcer for those teams, and I started getting together to plan an event for May 2018. We gathered at Stub and Herb’s and Manning’s over the weekend and were introduced on the field before a game against Michigan State. As part of this reunion, we developed an ebook on the 1968-70 teams.

Here are the folks who showed up for the reunion on May 11-12, 2018: Larry Carlson, Jim Chapman, Steve Chapman, Dave Cosgrove, Bruce Ericson, Chris Farni, Phil Flodin, Scott Frantzen, Lu Gronseth, Pete Hepokoski, George Hoepner, Gary Hohman, Mike House, Lightnin’ Gary James, Noel Jenke, Al Kaminski, Brian Love, Marv Menken, Bob Micheletti, Gary Morgan, Bob Nielsen, Jack Palmer, John Peterson, Gary Petrich, Jim Renneke, Bob Schnietz, Don Shellum, Stew Thornley, Jim Wallace, Mike Walseth, Bob Warhol, Greg Wasick, Gregg Wong, Roger Zahn, and Larry Zavadil.

Related: Ebook on the 1968-70 teams