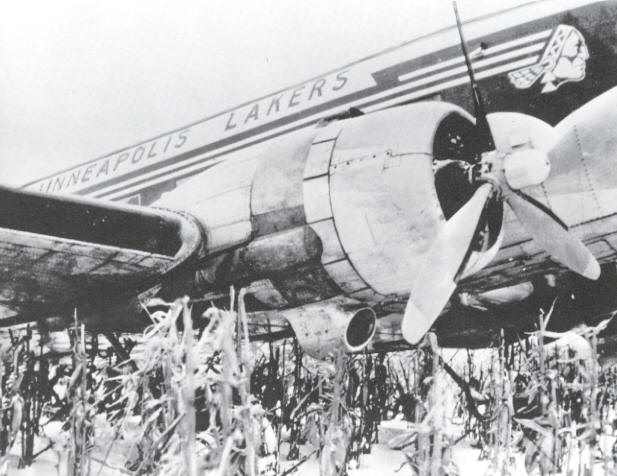

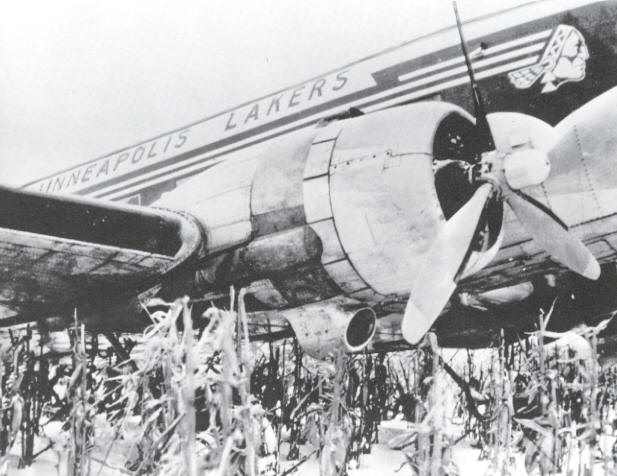

The Lakers’ plane in an Iowa cornfield

Minneapolis Lakers

Forced Plane Landing

By Stew Thornley

Author of Basketball’s Original Dynasty: The History of the Lakers

The Lakers’ plane in an Iowa cornfield

A groggy Bob Short picked up the phone around 1:00 the morning of Monday, January 18, 1960. At the other end of the line was an official of the Civil Air Patrol. “Are you the owner of the Minneapolis Lakers?” Short was asked. After responding affirmatively, he was given the news. “Your plane is missing.”

The private airplane carrying the Minneapolis Lakers basketball team and several other adults and children had left Lambert Field in St. Louis the night before. It had yet to reach its destination in Minneapolis and its whereabouts were unknown.

The Lakers had arrived at the airport around 5:30 following a Sunday afternoon loss to the St. Louis Hawks. Their DC-3, a converted World War II cargo plane that Short had purchased for the team, was waiting for them, but an ice storm had grounded all flights.

Pilot Vern Ullman, a retired Marine flyer who had seen action in both World War II and the Korean War, and co-pilot Harold Gifford checked the weather as the players waited in an airport dining area. The severe weather subsided somewhat over the next few hours, the players boarded the plane, and finally the decision was made to go. At 8:30, Ullman lifted the plane off the ground.

As soon as they were airborne, some of the players hauled out their makeshift card table and placed it in the aisle. No sooner had the first card been dealt, however, than the lights went out. “I thought it was one of our guys joking around,” said coach Jim Pollard, “but when I got to the front, I saw the co-pilot shining a flashlight on the instrument panel.”

The plane’s two generators had failed and the battery was drained of its remaining power immediately. “All the time we had spent on the ground, deciding whether or not to take off, had run the battery down,” recalled Gifford. “As soon as we lost the generators, we had no electrical power.”

The power outage left the crew with no guidance instruments except for a magnetic compass, which soon failed as well. They were without heat, defrosters, lights, or a radio, which precluded an attempt at returning to the St. Louis airport. Ullman pointed the aircraft in the general vicinity of Minneapolis and tried to climb above the storm to pick up the North Star.

“We were at 17,000 feet,” said Gifford, “but we still couldn’t get over the storm.” The altitude left the unpressurized cabin low on oxygen, and a few of the children became sick. The adults on board gathered blankets and coats to help the kids stay warm.

Nearly five hours after taking off, the plane had escaped the storm. But it had also drifted off course, and, with the gauges dead, Ullman and Gifford had no way of knowing how much fuel was left. “We thought we better find a place to land,” said Gifford.

Through the blowing snow they could see the lights of a town—Carroll, Iowa—below. They first flew past the water tower, hoping to find the name of the city. Snow had obliterated most of the name and all the crew could make out were the final letters, “O-L-L.” They then began buzzing the town in desperate search of an airport.

Ullman dropped the plane down and began following a blacktop road, hoping it would lead to an airstrip. With the strong winds creating a ground blizzard, as well as the visibility problems caused by the iced-over windshield, Ullman didn’t realize that the road had curved off and they were approaching a grove of trees. He finally spotted the danger and pulled back on the control column; the plane shot upward, narrowly missing the trees.

“We came within a couple of seconds of a crash right there,” said Gifford. “We were just about ready to hook a wing tip into those trees; it we had, the plane would have cartwheeled and we all would have died.”

After the near miss, they turned around and followed the road back into town. Unknown to Ullman and Gifford at that time was that the townspeople below were aware of their plight and were doing what they could to help. “We found out later that someone with a gasoline truck was trying to get our attention to have us follow him to the airport,” added Gifford.

Eva Olofson, Ullman’s widow, was on the flight and said she later received a letter from one of the residents, who said the police knew there was a plane in trouble and were telling people to turn their lights on to help the pilots see the town better. “I do recall the city lighting up like a Christmas tree, and it really helped.”

Because of the frost on the windshield, Ullman and Gifford had to keep the small cockpit windows on each side open. Parts of their faces were frostbitten from sticking them out the window.

The pair finally gave up hope of finding an airport and began debating their other options. They considered putting the plane down on the highway, but then they spotted a cornfield on a farm north of the city. Because of the wet weather the previous fall, the field’s owner, Hilbert Steffes, hadn’t harvested the crop. As a result, the stalks stood out in neat rows through the snow.

Both Ullman and Gifford and been raised on farms and knew that a cornfield would be free of rocks and ditches. Word was sent back to the passengers that they were going to land. Olofson says she remembers Elgin Baylor (who was not fond of flying to being with), lying down on the floor in back. “He said, ’If we’re going to crash, I might as well go comfortably.’”

Ullman jammed his head out the side window as far as he could and began the descent. Not only did Ullman put the plane down in a perfect three-point landing, he inadvertently hooked the tail wheel on the top strand of a barbed-wire fence. “The barbed-wire helped bring us to a stop,” said Gifford. “It was just like landing on an aircraft carrier.”

Olofson said she was so busy watching the pilots through the open cockpit door that she didn’t even realize that they were on the ground. Pollard agreed that it was a smooth landing. “I could have stood in the aisle with a glass of water in my hand and not even spilled a drop,” he recalled.

As soon as the plane came to a halt, the passengers broke out in cheers. By this time, the residents of Carroll had gathered by the side of the road at the edge of the field. Mistaking the cheers for screams and thinking the people on board had been injured, they began racing through the knee-deep snow toward the aircraft.

By the time they reached the plane, however, the passengers began emerging. “I think they wondered what was going on as they saw all these tall men stepping out,” said Olofson.

The townspeople helped the passengers through the snow to the road, where they piled them into cars and transported them to the hotel in town. Jim Pollard was the last of the Lakers to leave. He finally got into a long car and then discovered that his chauffeur was the local undertaker and that the vehicle was a hearse. “I had not been scared in the least while we were in the air or when we were landing,” said Pollard. “But when I saw that stretcher in the back of the car, I realized how close we had come, and I got the shakes for a few minutes.”

The passengers took a bus back to the Twin Cities the next day, but the pilots stayed behind. Following an FAA investigation, they also returned to Minneapolis, but a few days later, Ullman came back to pick up the plane.

“They were going to have someone else fly it out,” said Olofson, “but Vern wouldn’t let them. He said, ’I put it in there. I’m going to take it out.’”

The aircraft’s electrical problems had been repaired, and a bulldozer was used to flatten the snow and corn and create a runway. With several hundred people gathered along the road to watch and bid farewell, Ullman taxied the plane out of the cornfield and completed the journey started a week before.

Ullman was to die of a brain tumor in March 1965, but he remained a folk hero of sorts to the people of Carroll, Iowa. He returned two months later to be the keynote speaker at the annual convention of the Flying Farmers of Iowa.

Besides Baylor and Pollard, the Lakers who survived the ordeal were Tom Hawkins, Alex “Boo” Ellis, Hot Rod Hundley, Bob Leonard, Dick Garmaker, Frank Selvy, Jim Krebs, and Larry Foust. The DC-3 also survived and would continue to serve the Lakers.

Copyright 1989 Stew Thornley

Click here for a list of results and notes from all games played by the Minneapolis Lakers

Minneapolis Lakers Yearly Standings and Individual Statistics